Saturday 24 November 2012

Tuesday 30 October 2012

Turner Prize 2012

The Turner Prize 2012

The artists shortlisted for the 2012 Turner Prize: Paul Noble, Luke Fowler, Elizabeth Price and Spartacus Chetwynd, have created an exhibition which carefully, and recklessly, balances on the edge of insanity. Beginning with Noble’s methodical technical drawings and culminating in Chetwynd’s carnivalesque performances, the show intelligently gathers momentum, creating a sense of overall delirium.

Paul Noble presents a series of drawings of his invented town Nobson Newton, which he has been referencing since the 1990s, alongside faecal, marble sculptures. Each of his drawings, which are monumental in scale, begin with their title. This title is written in the centre of the page and is disguised as a building, anchoring his invented, microcosms of visionary architecture, modernism, turds and chaos at their inceptive roots. Nobson Newton itself is critically untouchable; Noble has devised his own formula and symbolic lexicon to a point beyond deconstruction. What he represents is almost irrelevant; it is the expunging of a calculated madness, which can only be fascinating. However, it is the muted meticulousness with which Noble details his fantasy town-planning which causes problems for the work.

Noble renders his drawings in very hard pencil. Thus, his drawings become vast expanses of pale grey. While the images are strange and fascinating, so much of their crude yet beautiful detail becomes lost. The desire to understand Nobson Newton is frustrated by its own suppressed portrayal. Conversely, the excremental sculptures are a lazy reference to his own symbolic language and feel crass and redundant. Noble’s offering is a confused mixture of compulsive insanity and restraint; a balance which could be brilliant but here feels underwhelming.

Elizabeth Price’s video installation The Woolworth's Choir of 1979, is an exhilarating assessment of history. Price splices together images of ecclesiastical architecture, grainy film footage of dancing girl bands and scenes of the 1979 fire in a Manchester Woolworths which killed 10 people.

Price intersperses the imagery with dry textual information, utilising fonts and graphics usually associated with commercial advertising. As the video progresses, the text is persistently intercut with footage of the Shangri-la’s, swaying in unison to an insistent, jolting hand-clapping and finger-clicking beat. The subjects begin to converge more and more until they are inseparable, and the helpless movement of a woman waving from a window in 1979, unable to escape the fire, is paralleled by a dance gesture of one of the Shangri-la’s, with Price’s words: ‘the greatest expression in the twist of a wrist.’

Similarly to Noble, Price adopts both absolute precision and obsessive frenzy. However, what Price manages to elicit is a 20 minute form of ecstasy, saturated with technology, information, history, rhythm, pace; a cinematic melodrama which leads you to an inevitable climax. The process is almost sexual, but Price’s decisions are highly intelligent, clinical and focused. It is a carefully orchestrated descent into madness. Whereas Noble’s approach is static and stultifying, Price’s momentum is unavoidable.

Luke Fowler’s work most explicitly references madness, with his film, All Divided Selves about Scottish psychiatrist R.D Laing. In comparison to the other works, this film is long and slow, running for 90 minutes. Fowler uses archival footage of Laing to detail his ideas, examine his fame and subsequent controversy, proceeding through digression rather than linear narrative. The definition of insanity is quietly usurped; the chasm between those diagnosed as mentally ill and those surrounding them confuses and surprises itself. For a piece of work which deals with such subject matter, its effect is subtle, manifesting with a slow reflectiveness. All Divided Selves seeps slowly into your system, unlike Price’s work which affects you so dramatically it becomes hard to breathe.

The final artist, Spartacus Chetwynd, is the first ever performance artist to be nominated for the Turner Prize. Described as medieval morality plays, Chetwynd’s performances have an engaging but threatening quality; the majority of which involve public interaction. While this encroaching on private space might ostensibly encourage a break down of the unspoken, but prevalent, modes of behaviour in the gallery space, it actually encourages further alienation. Chetwynd’s world, full of puppets, dolls, mandrake root gods, inflatable slides and medieval clowns, finds itself in danger of asserting a superiority rather than the harmless, humorous ‘tonic’ she intended.

While it is liberating to see an artist make decisions entirely based on an instinctive relationship to fun and humour, Chetwynd’s deliberately amateur approach jarrs alongside the deliberation of the other three exhibitors. Price’s precision highlights the brash nature of Chetwynd’s work; Fowler’s subtlety exposes her vulgarity, and Noble’s obsessive technique emphasises her own slapdash approach. However, this doesn’t seem like something which would phase Chetwynd; an artist who works impatiently and spontaneously, with no desire to make things which last.

This year’s Turner prize is not unanimously intelligent, nor is it entirely adept, but it is more engaging than it has been in years. Furthermore, it feels engaging on a human level rather than solely a critical one. The work ranges from crass to highly perceptive, liberated to restrained, quiet to clamourous and rational to completely unstable. However, the presentation of history as a malleable source is an undercurrent evident in all the works, rendering the exhibition both timeless and contemporary.

Kathryn Lloyd

commissioned by Line Magazine

http://linemagazine.tumblr.com/post/34660422317/turner-prize-2012

Thursday 25 October 2012

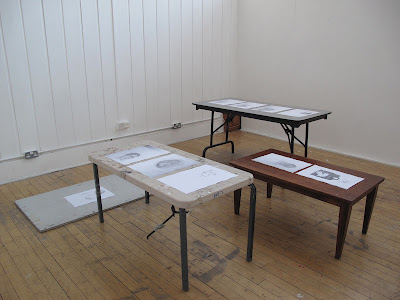

choice

upcoming exhibition

whitespace gallery, edinburgh

23 - 28 november

http://www.mcclureart.co.uk/artists/kathryn-lloyd

whitespace gallery, edinburgh

23 - 28 november

http://www.mcclureart.co.uk/artists/kathryn-lloyd

Wednesday 12 September 2012

AA-JE & The Transdisciplinary Studio

The Transdisciplinary Studio and Jérémie Egry & Aurélien Arbet

“[The studio] is most often a private place; it could be an ivory tower. It is a fixed place where objects are created that must be transportable.” - Daniel Buren

“Three laptops, a printer, and a very large table with lots of readymade meals - that’s all you need.” - Ryan Gander

A tension has always existed between the artist’s studio and the gallery or museum space. In 1972, Lawrence Alloway wrote an essay entitled Network: The art world described as a system, detailing a linear scheme in which “the density that a work accrues as it is circulated means that it acquires meanings not expected by the artist and quite unlike those of the work’s initial showing in the studio.”

Daniel Buren, writing three years later, wrote of the studio as crucial to a work’s intention, rendering it “totally foreign to the place where it is welcomed (museum, gallery, collection).” For Buren, any move away from the studio created an ever-increasing chasm; a paradox of place, for one reaches the ultimate contradiction: “either the work is in its own place, the studio, and doesn’t take place (for the public), or it finds itself in a place which isn’t its place, the museum, where it takes place (for the public.)”

Buren and Alloway’s analysis of the studio are both outdated models; an observation dogmatically made by Alex Coles in his recent book The Transdisciplinary Studio. Coles, dedicated to re-assessing the studio as an “operational vehicle for production” rather than a “trope or thematic”, begins his thesis by distinguishing the term transdisciplinary from interdisciplinary. In 1971, Roland Barthes detailed the notion of interdisciplinary practice as the point where “the solidarity of the old disciplines breaks down ... in the interests of a new object and a new language neither of which has a place in the field of sciences that were to be brought peacefully together,” resulting in the unease in classification. This has been increasingly evident in the design world, “in which attempts to account for the interface between art and design have led to a new interdisciplinary hybrid”; a way of working which attempts to apply traditional art characteristics onto design. This is not a new phenomenon, finding its roots in the early twentieth century with Constructivism, followed by De Stijl and Bauhaus.

However, Coles argues that this has now been replaced by a transdisciplinary model which eradicates any stable barriers, resulting in a space “that is at once between, across, and beyond all disciplines.” The difference then being that while ‘Interdisciplinarity’ acknowledges the combination or blurring of two or more disciplines, within ‘Transdisciplinarity’ those barriers are no longer acknowledged, even in their negation.

Coles classes this new studio model as part of a ‘post-post-studio age’, where artists and designers are no longer defined by their discipline, but the fluidity with which their practices move between them. Jérémie Egry & Aurélien Arbet, a collaborative pair who have been working together since 1999, ostensibly fit into this category perfectly. Their practice spans photography, fashion, design, curation, art direction and publishing, all with a strong internet presence. According to the duo, it is this fluidity which is their defining characteristic: “We consider each of our projects complimentary. It’s a great pleasure for us to move between different mediums and not be a ‘bored specialist’”. In the past thirteen years Egry and Arbet have founded HIXSEPT, a male clothing brand which blends tailoring and experimentation, established alongside others JSBJ - Je Suis Une Bande De Jeunes - a collective which supports and publishes contemporary photography, while also exhibiting their photographic works, both collaboratively and separately.

The notion of the transdisciplinary studio is inherent within Arbet and Egry’s practice. On a practical level, the duo are split between New York and Paris, so their projects unfold through Skype conversations and emails, and can involve a large number of people across various fields. Additionally, the broad spectrum in which they work is mostly facilitated by the accessibility of an online network. For a clothing line to so seamlessly blend into artistic experimentation, or a publishing house to retain an inherent availability, the openness of the internet seems vital. With both their use of the internet and the transdisciplinary approach, Arbet and Egry seem to have collapsed the hierarchy that is complicit in the studio to gallery narrative. The work space and gallery space have united; they are one and the same.

Earlier this year, Arbet and Egry contributed to an exhibition entitled GOOD AS NEW, with David Brandon Geeting, Nicholas Gottlund, Bruno Zhu and David Zilber at Ed. Varie gallery in New York. The show was brought together by Geeting who found an online interview in which Ziber expressed an interest in participating in a “dream show” with the above-mentioned artists. From that point, Geeting initiated a group email that linked the participants together and ultimately realised the show. Furthermore, their projects – such as JSBJ – create a platform which facilitates the work of others as much as their own; something they consider the internet “the perfect medium” for: “It was also a good way to curate and propose our own vision about contemporary photography; to create a space with new directions and experimentation.”

In The Function of the Studio, Buren classed the studio, at its most simplistic level, as “a fixed place where objects are created that must be transportable.” Coles’ re-assessment of the studio as an ‘operational vehicle’ hints at the employment of the internet as a tool for both creating and sharing work, but does not categorically connect the two. Instead, he remains rooted in Buren’s notion of the ‘fixed’ studio workplace as the hub of activity. However, there is an unmistakable parallel between the transdisciplinary studio model and the platform of the internet. They both offer unity, dissolving the barriers which previously separated disciplines, discourse and knowledge. The internet is the ultimate transdisciplinary workplace.

However, while they are aware of the success the internet has afforded them, Arbet and Egry do not consider themselves ‘internet artists’: “It is now a large part of our work, and our way of showing and spreading it ... [However] we both have our traditional studio spaces where we meet to complete projects.” Thus, they class themselves as “halfway between the hammer and photoshop”. The aims of JSBJ remain the same, but they have recently moved away from online portfolios and now produce books and exhibitions. They state that “often the internet is very light and quick and does not dig deep enough. We wanted to step back a little and propose some more assertive projects”. It appears that the desire for ‘real stuff’ is still strong in their practice: “It feels good to not just work in the fuzzy, abstract internet realm.”

Arbet and Egry have subsumed the internet into their practice. However, their awareness of its ‘non-place’ nature has succeeded in retaining a necessary physicality within their work. Regarding Coles’ assessment, these two appear to sit somewhere between the interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary. They view themselves as “part of a generation that is in between”, having grown up with books, studios and meeting people, but also witnessing the inception of the internet and utilising it both practically and conceptually. Their photographs appear on blogs, websites and gallery walls. The space between the studio and gallery has certainly lessened in one sense; it does not need to travel far, and the viewer can experience a work in at least three different ‘realms’. However, if the viewing space can no longer be dictated by the gallery, but is public online, then it can be viewed anywhere and anytime. Though this is a virtual experience and not a ‘real’ encounter with the work, doesn’t it make Buren’s ever-increasing chasm between studio and public appearance, even greater, and without limitation? Is the work still “totally foreign” if it is being viewed in a ‘non-place’ rather than ‘taking place’ somewhere fixed?

Thus, Buren’s paradox of place has been replaced by a paradox of ‘non-place’: is the chasm greater because its point of inception and culmination are one and the same, or is this chasm eliminated by the vastness of the internet platform? The work is constantly taking place for the public; for every public and every place.

Arbet and Egry’s method of working has retained a desire for physical projects, despite their intelligent online presence. In their own words, “it’s just the way human beings are. We still need to talk, meet and discuss things. The internet allows us to meet more people and find opportunities, but it can be too much stuff happening all over the place sometimes.” The success of their work is that it manages to flourish both in ‘place’ and ‘non-place’; entirely in control of the unpredictable chasm between a work’s beginning and end-place.

Kathryn Lloyd

This summer Arbet and Egry will be bringing together all of their team's creative services in a single studio entitled Études. Études is a collective based in Paris and New York, and is the evolution of the clothing brand Hixsept and the publishing house JSBJ. Études designs and produces men's contemporary fashion, artist books and will offer its services of creative direction, visual brand identity and photography skills to clients, brands, institutions and magazines.

Etudes N°1 Collection will be available from September 2012

The three first Etudes Blue Books will be released at the New York Art Book Fair

Bibliography

Alloway, Lawrence 1972. ‘Network: The art world described as a system’, Network: Art and the Complex Present, 1984 (UMI Research Press)

Buren, Daniel 1975. The Function of the Studio (http://www.khio.no/filestore/buren_studio.pdf)

Coles, Alex 2012. The Transdisciplinary Studio (Sternberg Press)

First published in Line Magazine, edition 9, Re:line

www.linemagazine.co.uk

www.linemagazine.tumblr.com

Wednesday 5 September 2012

Thursday 26 July 2012

Saturday 14 July 2012

Thursday 12 July 2012

Tuesday 26 June 2012

Wednesday 20 June 2012

Wednesday 23 May 2012

Thursday 10 May 2012

Saturday 5 May 2012

Friday 27 April 2012

Sunday 1 April 2012

poets and babies

collaboration with rachael cloughton

using photocopies of drawings, text pieces and rachael's films

www.rachaelcloughton.com

using photocopies of drawings, text pieces and rachael's films

www.rachaelcloughton.com

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

-WEB.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)